As I’ve been reading papers, one of the things I’ve thought about is the different types of papers or articles a graduate student might be interested in writing and publishing. And as I was trying to find answers to my own questions, I realized that no one had consolidated anything into one location (that I could find, anyway). Therefore, I decided to craft a “beginner’s guide,” if you will, to the world of scientific publications : written by a beginner, for beginners, and edited by the experienced.

Guide Contents:

- Recognizing Publication Types

- Paying the Price

- Choosing Your Text Editor

- Measuring Your Success

Recognizing Publication Types

I’ll pull definitions of article types from a few journals in different fields, just to show the diversity and realistic requirements.

Research Papers

Hopefully if you’re a graduate student, you’re intimately familiar with these papers by now. You probably averaged somewhere between 1 and 5 of these a week depending on how new you are/were to your graduate field of research. I was completely new to both fish and biorobotics; there were some weeks where I read one paper and some when I read 30 or more. No, I’m not exaggerating.

However, “research papers” is a pretty broad category that encompasses a lot of different types of publications. Which type you publish probably depends on factors: how urgent are the results you’re presenting (should they get out ASAP or can you wait the few months to a year it might take to publish normally?), how much work you actually have to type up (2-3 pages or 15-20?), how amazing the results are (will people outside of your field or the scientific community think it’s cool?), and how novel the methods are (same-old same-old or did you invent a new revolutionary model?).

Standard Research Article

The standard article is probably what comes to mind when you think “research paper”. It should be pretty obvious to you why you would want to write one (and more) of these. “Publish or perish” in academia. If you spend time on a project and it never gets published, that was essentially wasted time. As a grad student who wants to remain in academia after receiving their PhD, we don’t have the luxury of not publishing, or spending time on projects that might not result in anything. This is touching on a finer point: plan your projects well.

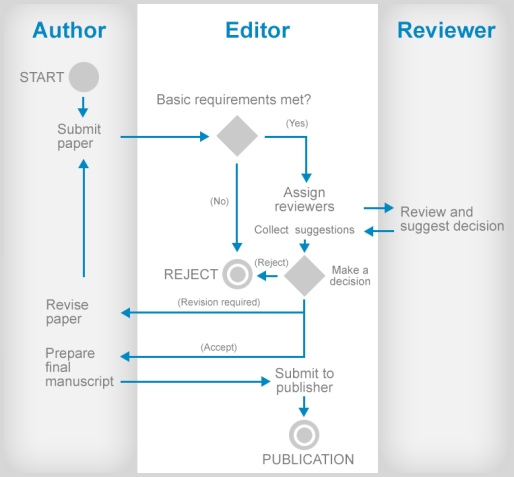

Research articles are generally at least a couple of pages in length and are written with the intention of relating research results. The standard format is Abstract-Intro-Methods-Results-and-Discussion (AIMRAD). How long it takes for an article to go from submitted to published depends on a couple of factors, e.g. how many reviewers you get (bigger field, more reviewers, generally), or how many other submissions there are. A journal can only publish so many articles; a line has to be drawn somewhere.

When we were trying to get my undergrad papers out, the journals we submitted to were small because our field was small, and we only had one reviewer per paper. It took about 3 months to do initial submission, respond to referee comments and resubmit, and final publication. For larger journals where you might be waiting on two or three referees, you could wait 3 months just to get the initial comments back. If you have to do the submit-revise-resubmit process more than once, those months really add up.

When publishing a research article, or anything really, it’s important to pick the right journal. You wouldn’t publish an article about keystone species ecology in an immunology journal. The journal’s audience wouldn’t really care about keystone species. Even within a certain field, different journals focus on different things.

For instance, with my pneufish, the journals we’ve considered are Journal of Experimental Biology (JEB), Bioinspiration & Biomimetics (B&B), and Soft Robotics (SoRo). JEB has a requirement (thanks in part to George) that all papers must include a live specimen experiment. My pneufish isn’t a living organism, so I couldn’t submit my paper to them. Soft Robotics would be a good one, but I do want to have a significant “biology” facet to my paper, extrapolating the pneufish’s movements to actual fish. The audience of SoRo might not care that much about a portion of my paper. Thus, I will most likely submit to B&B first. Hopefully it won’t get rejected.

This example touches on another point. Not only do you have to pick a journal targeted for the audience you want to communicate your research to, but you have to fulfill the basic requirements of the journal. This can mean anything from content of research (e.g. JEB requiring live animal experiments) to number of figures, and each journal has their own list of requirements.

———

Tangent Time: Different Labs, Different Styles

Different labs have different approaches to writing papers. Some favor the “publish as you go” method. One benefit to this method is that when it comes to defending your thesis chapters, they’re hopefully already published or in review, and thus there’s not *too much* the committee can argue with. What are they going to say, the chapter was good enough to publish but not good enough to pass the committee?

The second benefit is that when you start looking for post-doc positions (or whatever else you are interested in), you already have several publications under your belt. In a time when funding is scarce and people want to hire people they know can produce results and papers, having a nice “Publications” section on your CV is a sweet thing to be able to point to. And you’ll be able to reassure whoever’s hiring that you won’t have to devote any time to writing up your grad projects during your new job.

Publishing is also good for our mental health. Joking aside, we’re in it for the long haul. It’s something we accept when we decide to go to grad school–five or more long years of being indentured servants to our science–but it’s not something anybody can really prepare for mentally. It’s like being on a treadmill with no dashboard and training for a marathon. You’re going, sometimes walking and sometimes running, but you have no real measure of how far you’ve come or how far you have yet to go. Publications are milestones you can create for yourself. Having something concrete to show yourself that what you’re doing is not only worth it, but that you’re actually making progress, is beyond priceless in a grad student’s world.

Publishing is also good for our mental health. Joking aside, we’re in it for the long haul. It’s something we accept when we decide to go to grad school–five or more long years of being indentured servants to our science–but it’s not something anybody can really prepare for mentally. It’s like being on a treadmill with no dashboard and training for a marathon. You’re going, sometimes walking and sometimes running, but you have no real measure of how far you’ve come or how far you have yet to go. Publications are milestones you can create for yourself. Having something concrete to show yourself that what you’re doing is not only worth it, but that you’re actually making progress, is beyond priceless in a grad student’s world.

Though few in number, some labs do exist where the PI wants you to focus on research and having a cohesive story before writing up your chapters as publications. The obvious downsides to this are that you don’t get a lot of writing experience during your degree and that you’ll be working on publishing your grad work during your post-doc. Hopefully during your post-doc, you’d be trying to publish your post-doc work, you know? According to the more experienced, if you’re trying to publish your work and you’re in another lab, possibly in a different state or country, then it’s definitely harder to jump back into lab to fix or test things you decide need to be fleshed out.

The benefit is that you’d probably be able to write a series of papers that flow really well together. If you’ve graduated and you have your thesis all done and checked over, publishing those chapters is, theoretically, a short step. The reality, however, is that going from chapters to publication is so much harder than going from publication to chapter. It is a heck of alot easier to add paragraphs and figures in than it is to take paragraphs and figures out. Chapters don’t really have too many limitations in terms of page length, number of figures or citations, etc. Publications do. It is much easier to write for the strict regulations first and then add material later than it is to take material away.

If you’re interviewing for grad labs, definitely ask the lab members and the PI about this. If everything else about the lab fits your style but the publication approach, then I doubt it’ll be a deal breaker, but it’s not something you want to be blindsided by.

———

Letters/Short Communications

Depending on how much work you have to write up and the speed at which you want to publish your results you might decide writing a letter or short comm better suits your needs.

Here are the various definitions:

- JEB: “…short, peer-reviewed articles (2500 words) focusing on a high-quality, hypothesis-driven, self-contained piece of original research (3 figures max) and/or the proposal of a new theory or concept based on existing research. They should not be preliminary reports or contain purely incremental data and should be of significance and broad interest to the field of comparative physiology.”

- PNAS: “…brief online comments that allow readers to constructively address a difference of opinion with authors of a recent PNAS article. Readers may comment on exceptional studies or point out potential flaws in studies published in the journal. …Letters are limited to 500 words and 10 references, and must be submitted within 6 months of the online publication date of the subject article. “

- Nature: “…short reports of original research focused on an outstanding finding whose importance means that it will be of interest to scientists in other fields. They do not normally exceed 4 pages of Nature, and have no more than 30 references…3-4 figures.”

After going through the various Google results, it seems to me that people use “Short Comm” and “Letter” interchangeably. The definitions flip flop a bit, in general. It might depend on the particular journal, but because of this ambiguity, I’ll just assume they’re one in the same until I learn of a more concrete distinction.

The letter I’m most familiar with is the “new/urgent discovery” type of letter. If something is urgent (e.g. “San Andreas Fault Earthquake Imminent!”) or revolutionizing either for a specific field or science in general (e.g. “Dinosaurs may have been dying out before asteroid hit”), you might consider writing a letter.

For the average graduate student, I’m going to wager that letters won’t be your publishing MO. Writing these is harder because you don’t have the standard format to rely on (they’re written more as prose than a standard research article) and you have to be super concise, with the harsh page/word limits. Definitely go for it if you think you can, but just be aware of the different requirements.

Methods Papers

Methods papers, sometimes called Technical papers, are something I think of as a subcategory of research papers (because methods is a pretty important part of research), but they can be considered a completely separate category, I suppose. In fact, some journals are devoted solely to publishing Methods papers (e.g. Nature Methods, Journal of Biological Methods). Again as you probably deduced from the name already, Methods papers are written to describe a newly developed method, technique, software, or model and to relate the need for it, the differences between the new method and the old method(s), a validation analysis (how you can trust the results are meaningful and accurate), and how it can be applied to new or old systems.

You might write a Methods paper if a) you’ve actually developed a new method, technique, software, model, etc., and if b) enough work went into the development and validation of the method that there’s enough material to make its own paper, and/or if c) you’re submitting to a journal where a methods section generally isn’t even included in the article, but stuck in the supplementary section. In the latter situation, it would be so easy to just say, “This new technique was applied as described in MyName et al. 20XX in Journal of Biological Methods” and go directly to results. That way, your methods paper gets a citation (*wink wink*) and people might be intrigued enough to actually go read it to find out exactly what the new method is.

One benefit of writing a methods paper is that all that work you did to create and validate your methods before even starting to use them can actually see the light of day. You can include all the cool details that you might have to skip in a normal paper. The downside is that you actually have to write another paper, which takes time and effort. It’s really up to you and your PI to decide if it’s worth it.

Review Papers

Review papers don’t present any new research, but seek to coalesce and summarize recent research about a topic or sub-field. The main requirement to write review papers is to do a heap ton of reading beforehand. However, if you’re already reading a heap ton of papers in your field as part of your indoctrination into your lab, then you’ve got a head start. Review papers are peer-reviewed like anything else in the publishing world, and can be a good deal longer than the standard article.

- JEB: …”predominantly commissioned articles that aim to provide a timely, insightful and accessible overview of a particular field or aspect of experimental biology research.” There are two “size” options: 4500 words and 5 figures to look at a very specific topic, or 7000 word and 8 figure limit that can talk more broadly about a subject and bring together data from different fields. (To give some scale, this blog post is roughly 6700 words, so I guess I’m getting good practice!)

- Nature: “….focus on one topical aspect of a field rather than providing a comprehensive literature survey. They can be controversial, but in this case should briefly indicate opposing viewpoints. They should not be focused on the author’s own work. Language should be simple, novel concepts defined and specialist terminology explained.” For size, reviews are capped at 8 pages and 100 references.

- Neuroscience: “…short articles (3,000 to 10,000 words in length), not exhaustive reviews, that are intended to either draw attention to developments in a specific area of research, to bring together observations that seem to point the field in a new direction, to give the author’s personal views on a controversial topic, or to direct soundly based criticism at some widely held dogma or widely used technique in neuroscience.”

Multiple post-docs in my lab said grad school is the best time to write a review paper simply because you do have more time to read papers intensively, maybe do a meta-analysis, and write the review. Additionally, because they don’t present new research, you don’t really have to do any research (as in work research, not reading research) in order to write one. It can be a publication you work on early in your grad career, and because review papers are often cited, in introductions especially, it would be an easy way to ramp up a lot of citations during grad school.

Personally, I will aim to write at least one review paper in graduate school. I know that I’m in the best position to receive help and guidance while writing one now, in grad school, than I ever will be again (and that goes for a lot of things) and I have the time and the motivation. If I don’t write a review paper after graduate school, then so be it, but I’ll at least have the experience just in case I should ever want to. With all the reading I’ve been doing, I might be in a good position to discuss all the fishy robots currently being used, compare and contrast them to each other and to live fish, and perhaps do a meta-analysis on the results.

Once you leave grad school, you read mostly to keep up with the field. It makes sense generally, but I feel that it’s person-dependent whether someone will want to write a review paper once they are a post-doc or professor. For instance, I know George has written many review papers since he became a professor, but he’s probably a very notable exception. (He’s written a LOT of review papers.)

Perspective/Commentaries

Perspectives differ from review papers in that review papers look backwards, while perspectives are trying to look to the future. Perspectives are again peer-reviewed and go through the standard publication process.

Some guidelines:

- JEB: “…commissioned, peer-reviewed overviews of a subject or novel idea that convey the author’s perspective on the topic. Authors are encouraged to introduce new or potentially controversial ideas or hypotheses, but opinion and fact must be clearly distinguishable. Commissioned authors are requested that Commentaries are a maximum of 4500 words in length (excluding the title page, summary, references, figure legends and boxes), with up to 5 display items (figures, tables or boxes).”

- PNAS:”Authors are invited to present a viewpoint on an important area of research. Perspectives focus on a specific field or subfield within a larger discipline and discuss current advances and future directions. Perspectives are of broad interest to nonspecialists and may add personal insight to a field.”

I’ve heard from several people in the Lauder lab that grad students are encouraged to write perspectives, but I’m not sure who exactly is encouraging this. In order to write a perspective, you first need perspective. It can be hard as a grad student to first have such a good understanding of the field’s big picture, and then to have a novel/useful idea that’s never really been addressed in the field before. And then to write a perspective suitable for Science or Nature, where the ideas you put forth should be applicable to all of science–it’s a tough thing to achieve.

Commentaries are essentially responses to specific articles, and most journals say “don’t call us, we’ll call you” when it comes to writing and submitting these. So, I wouldn’t worry too much about writing a commentary until later in your degree.

White Papers

White papers are similar to articles, but written for an internal audience. They don’t ever really get published in a journal, but they can be made available on department/company/organization websites. I’ve only really seen white papers in physics and they were internal reports to large teams. I did some work for a group building a telescope prototype and white papers were technical reports written to others in the group about the design and performance of some piece of technology. They’re also used in businesses as sales or marketing reports (sometimes called ‘grey papers’). If you’re involved with conservation, or human health, you’ll probably come across these quite a bit more frequently than other fields would.

Conference Proceedings

Proceedings are weird. They are papers written about research exclusively for presentation at a conference. For SICB, everybody has to submit an abstract regardless of whether they are presenting a talk or a poster. The abstracts are collected into an online book of sorts and are available to the public. Instead of abstracts, some conferences require papers. The proceedings I come across most often are from IEEE, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers and a lot of engineers who build robots end up presenting their work there and thus have to put out a proceedings. It’s not terribly common in conferences outside of engineering to have proceedings requirements and I doubt I will ever have to write one myself. Maybe co-author on a project at some point, if we involve an engineer who would like to present at one of them, but that’s it. Sometimes the research presented in proceedings never goes on to any other form of publication.

TL;DR: If you’re not going to engineering/robotics conferences, you’ll probably never need to worry about these.

———

This list is far from comprehensive. There are a lot of different types of publications I didn’t go into simply because I don’t think they’re as common or as useful to know about. If you are starting to write projects up and you have a decent idea of what journals you could send the article to, go to that journal and look for their specifications. Every journal does something just a bit differently from the others, whether it’s requiring people to submit their articles in Latex or Doc exclusively, labeling tables and figures a certain way, line numbers on submissions, etc.

Paying the Price

I wanted to very briefly touch on the fact that publishing costs money. The figure below shows how much it costs, on average, to publish one article.

Open access journals are journals where the content is made available online for free. Hybrid journals are journals where some of the articles are made open access for a fee, whereas you could choose to not pay the fee and have your article behind the paywall. If you’re a student, chances are you consider most journals to be “open access” because as long as you link to them through your university library, you can read them without paying the fee. The university pays it for you (and this helps explain where part of your tuition money is going).

However, if you’re submitting to a journal, then very little is free. For some journals, having a subscription is a necessary prerequisite to publishing, and the subscription cost might even be equal to the cost of publication. If you have the subscription through your university, then, essentially, you can publish in those journals for free. The downside, of course, is that your article is behind a paywall. If you’re submitting to a journal that publishes an actual journal edition, you’re also paying for the paper (sometimes cost/page, sometimes cost/XXX words) and the ink. If your article requires colored ink (for figures, perhaps?), then that costs more, too. If you’re submitting an article for an online journal, then colored ink cost doesn’t really matter much, however.

The most common options I’ve seen are Gold Open Access and Green Open Access. The above images are examples from Elsevier’s sites. I know for JEB, the price difference is roughly $3100. Elsevier has a massive compilation of journals, their type (hybrid/OA), and the fee.

The most critical difference here is that Gold articles are available online immediately upon publication, whereas Green articles aren’t available until 6 months after publication. You might think, well, it still is published in paper right away, and you’re right…but how many people still have paper subscriptions to magazines? How many people do you know go to the library each month to read the new edition of Whatever Journal? Not many. If you want your information out in a timely manner and seen by the majority of the journal’s audience, Gold open access is pretty much the way to go.

Now, according to the post-docs in my lab, no graduate student should ever really have to pay these fees themselves. If a PI is on the paper and they have grants, there should be money allocated from the grant to cover publication costs. Even as a post-doc, if you’re working off a grant, the grant should cover the costs. The gray area is if you’re publishing as a single author, where your PI isn’t listed in the author line. That’s probably a case-by-case situation.

This section was just to bring attention to the fact that publishing is a necessary but costly action. If you want to know more, let me know and I can do some more digging.

Choosing Your Text Editor

I grew up, academically speaking, in a LaTeX (lay-tech) household. In the GT physics department, it was pretty standard to write lab reports, papers, even weekly homework sets in LaTeX . In some classes, it was required. There are several reasons for this. One is that Linux is probably the dominant platform in the GT physics department, and LaTeX is such a step up from any Word-facsimile Linux/Mac distros have. The second is that Word is a pain in the ass when you try to format things. Change one image and the entire document is blown to pieces, right? The third is that a number of physics journals only accept .tex submissions, they even have their own templates for authors to use. So, professors saw it as part of the professional training process for students to know how to use LaTeX .

However, the publishing world doesn’t run on LaTeX ; Word is still the dominant platform for writing manuscripts. Like anything else in the world, LaTeX is better at some things than Word, and Word is better at somethings than LaTeX . It just so happens that the things Word is better at are useful when it comes to publishing.

For those unfamiliar with LaTeX and want to know more, watch this video.

LaTeX is the absolute best at formatting equations. Some of the more quantitative fields (e.g. astrophysics) have given up submitting papers using Word simply because of this feature. LaTeX is also great at providing absolute control over all formatting issues: regulating and formatting references and bibliography, anything at all to do with headers, margins, titles, and controlling figure/table design, placement, and format.

However, LaTeX doesn’t really have spellcheck. At least not in desktop programs. Online programs such as Overleaf or ShareLaTeX do have spellcheck. LaTeX is also not as mainstream. People know how to work a .doc file. You don’t need to know anything special to use it. Using Word is easy because of the GUI, sometimes called a “What You See Is What You Get (WYSIWYG)” editor. LaTeX does away with the traditional GUI and focuses more on personalized functionality. What you see is what you put there. Because of this, LaTeX comes with a learning curve. It’s more similar to a coding language than it is a text editor, and therefore it comes with the same obstacles as learning a language does (e.g. syntax, commands). This learning curve does take time to overcome (maybe a day to get the hang of it, a week to become proficient at). But if you’re strapped for time and you’re later in your career, I could see how one might reason learning LaTeX isn’t worth it.

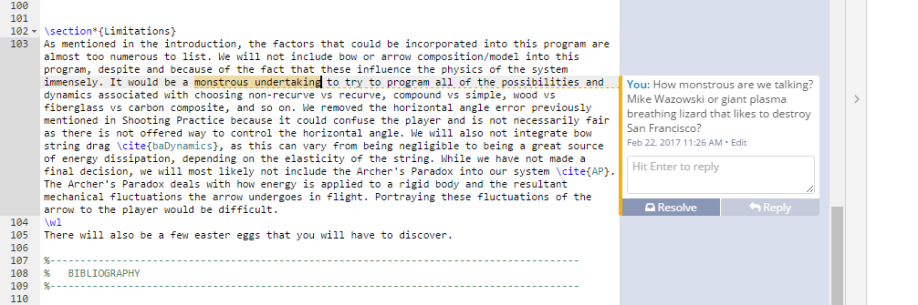

The main benefit of using Word to write manuscripts is the track changes feature. When I started writing this blog post, neither Overleaf nor ShareLaTeX had anything resembling Word’s track changes feature. They allow collaborative writing and version history via Git. However, as I was editing this post, ShareLaTeX started beta-testing a track changes feature. It’s not free. Student access is $8/month ($80/yr), I think, with normal membership rates at $15-$30/month (and between $180-$360/yr), based on your needs (e.g. number of collaborators).

I actually emailed ShareLaTeX and asked why they did this. It turns out that commenting is available to all users, paying or otherwise, because this feature is most useful for solo writers. However, historically, all their collaboration-based features are for members only. Thus it made sense that things like suggestions or track changes, which are of more use for collaboration projects, also fall behind the paywall. That kind of sucks, but it’s a pretty big step in the right direction. Now that ShareLaTeX has proven that it’s possible to have track changes in a LaTeX interface, hopefully we’ll see this become a more common feature.

Back to the main point though: because of these reasons, LaTeX just hasn’t become the mainstream writing software yet, which is regretful. As I said, there are a few fields and journals were LaTeX is standard; these are likely to be heavily quantitative fields. LaTeX is just so vastly superior when dealing with equations that these fields have outright dropped Word. A few biology journals will accept .tex files (e.g. Nature, Science, JEB) and some even have their own templates (e.g. PLoS), but they all say that everything will be converted to Word during the editing process, and at that point, a lot of people will ask why they should even bother with LaTeX at all. I still have hopes that people will see the light.

I will write my thesis and whatever individual projects I do in LaTeX because I believe in its superiority. And I’m kinda stubborn.

Measuring Your Success

It sucks to say, but publishing isn’t enough. The old adage “Publish or perish,” is something I’ve heard reinterpreted as “Publish in high impact journals or perish.” As in any professional sport where players are competing for contracts (read: grants) and spots on good teams (read: jobs), people want to know your stats. In academic publishing, stats can be divided into three main components: the journal, the article, and the author.

Not all journals are created equal. They’re organized kind of like a pyramid, with a few journals at the top and a lot more in each subsequent level. A journal can be assessed quantitatively but because different people consider some aspects weightier than others, there are a number of different assessment types. I’ll discuss the two top ones: the impact factor and the eigenfactor.

The most common stat to hear in reference to a journal is the impact factor (IF), which just compares the number of papers published by the journal to the average number of citations each published paper receives. The IF is generally assessed from field to field, which can be both useful and not depending on what information you seek. The reason why Nature and Science have such high IF values is because they reach people in multiple fields; they’re collecting points from multiple teams, if you will. But once you get past those big-name journals, IF does become very field-specific.

Some cons are that everything is weighted the same (reviews are often cited way more often than an average article; this is why the blanket ‘average citation number’ is an issue) and the IF includes self citations. Each year the rankings are published in the Journal Citation Report.

An eigenfactor ranking basically does the same as the IF but it is structured to give citations from highly ranked journals more weight and is calculated over 5-year spans, not over single year periods. It also eliminates self-citations and articles referencing other articles in the same journal. The eigenfactor is field-independent, which can be a pain if you’re trying to search a single field. However, the eigenfactor is free to access, while the IF costs money to determine.

To read more about these two, here’s a nice study that compares the accuracy of them. More people have issues with the IF than with the eigenfactor, which has shown to be a more accurate measurement. However, given the increasing use of the internet, both of these metrics are waning in their usefulness, and I’ll come back to that in just a moment.

Now, at this point, I’ve written and deleted several paragraphs that go into why the impact factor is bad. However, I’ve decided that’s a bit beyond the scope of this already large guide. If you want to read some articles on that, I suggest looking in Appendix B at the bottom of the blog.

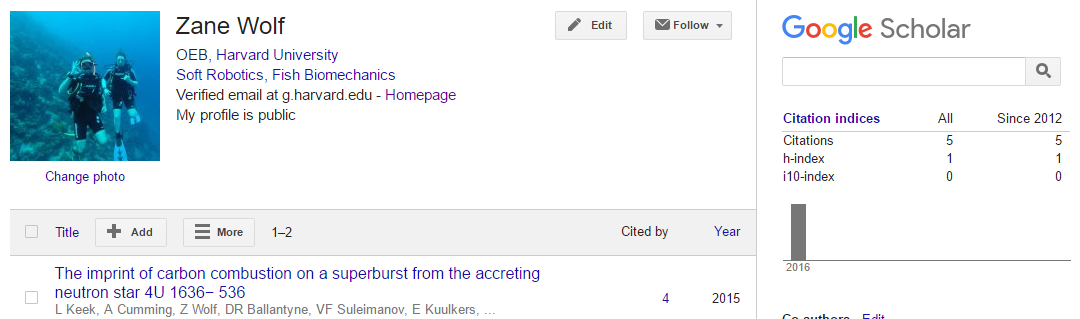

Authors are most often assessed using something called the h-index. It’s pretty simple: the number of papers (h) with more or equal citations to h. If you have one paper that has been cited one time, you have an h-index of 1. If you have an h-index of 12, then you have at least 12 papers that were cited at least 12 times. You might have 2 or 3 papers that have 200 citations and you might have a few papers that were only cited once or twice, but as long as you have 12 papers that were cited at least 12 times each, then your h-index is 12. As your papers get more citations and as you publish more, your h-index will change.

The nice thing about the h-index is that is does not matter what journal you published in, only that the article itself was useful enough to be cited. One of the problems is that the h-index is calculated using only articles indexed by Web of Science.

The second problem with the h-index is that is it not really fair to new publishers. I’m going to borrow the example given here. A grad student who may have 5 published papers each with at least five citations would have an h-index of 5. However, what if a student only had 2 publications, but each of those publications were high-profile and have 50 or 100 citations? That student’s index would still only be 2. The h-index is useful for the well-written, well-established researchers, but not for the researchers just starting out.

To help solve this issue, Google Scholar came up with the i10-index. This number is basically the number of papers with at least 10 citations. So, with the above example, the first grad student would have an i10-index of 0 while the second has an index of 2, which more accurately reflects the students’ articles’ impact. This index is only available in the Google Scholar profile (if you don’t have one, you can make your own).

Another site becoming more and more popular among scientists is ResearchGate. I joined it back during my first years of undergrad because I needed access to a paper, and it’s become more widespread since then. RG is an academic version of LinkedIn. It’s not quite as complete as Google Scholar profiles is, but it’s getting there. They also do statistics and whatnot. It’d probably be useful to make a profile here and update it somewhat regularly. It also has a Stack Exchange-esque component to it, where people ask questions about features of the academic community and people can respond. It’s pretty good.

In terms of article impact, things are changing. Articles themselves can be assessed using the h-index and the impact factor, but in an internet-based world, maybe these factors don’t give you the complete picture. Altmetrics, or alternative metrics, is a word I just learned about. Altmetrics try to take in references in blogs, downloads, social media time, normal citations as well as wikipedia citations, average viewing time on an e-article, and times included in a reference manager, into account. This last bit is partly made possible by Mendeley and other such softwares. Because everything on Mendeley is connected, people can look to see how often their article was downloaded and read by other users. They can even look at the demographic of who is reading their papers because Mendeley users can specify what they are in their profiles (e.g. “my paper was read by 10% professors, 45% grad students, 20% post-docs, 25% unknown”). In general, altmetrics provide users with a general idea of how pervasive their study is not just through the lense of journals and citations, but through the multi-faceted internet, as well.

Right now, altmetrics is still on the rise, but I wager it won’t be long before it becomes a well-known standard.

In terms of what these metrics mean when searching for a job, a post-doc in my lab said the following: Those hiring tend to look at these 3 metrics the most: 1) number of papers published, 2) the quality of the journals (as measured by impact factor or reputation), and 3) number of overall citations AND/OR the rate of publications (pubs/year).

The publication rate per year is something to keep an eye on, but it may not make or break an interview. For example, let’s say you published as you went during grad school and you got a post-doc right after graduation. If you didn’t have any more chapters that required publishing for your graduate work, and you’re just now starting a new job, then it might be a while (maybe a year or more) before you have another project built up enough that you can publish on it (maybe a good time to write a review paper or a perspective, perhaps?). It’s possible you could end up with a “publication gap,” a year on your CV where you just didn’t publish much. As long as you were working on stuff and the publications from that work are already published or in the works by the time of your interview, you should be good.

Additionally, if a person hiring looks at your CV and sees that you published a lot of papers just in the past year, then they might understand if your citation-based metrics aren’t all that amazing. From the time you publish a paper, it’d probably be at least 6 months if not longer before papers citing your work are published.

As I said in the beginning, this was just a basic guide pulled together from what little experience I have, research I’ve been doing on the topic, and the experiences and advice related to me by those farther along in academia. As I start writing publications of my own, I’ll aim to write more “Publication Type X: In Depth” blogs describing the learning process and the details involved with going from idea to published manuscript, but those are still a long ways off.

Finally, I would like to thank the post-docs of the Lauder Lab for their official comments and insights on this blog, and the rest of the Lauder lab for the bits of advice I picked up and stored for later.

Cheers,

Z

Appendix A

This was a fun group project two other students and I created for a Computational Physics course at GT. We created a java game with two levels: Shooting Practice, where the player shoots against a target, and Adam’s Apple, where the player tries to shoot a fruit off of Adam’s head. The player could select what planet they were on and they could choose different sized fruit to aim at (making it less lethal to Adam). The point of the game was to demonstrate projectile motion to a grade/middle school audience. The planet chosen influenced gravity and air resistance, and the player could set initial angle, initial force, distance to target/Adam, and the center of mass (because they could also set the weight of the arrow head, the length of the shaft, and the number of fletchings). We thought about making it super complicated and going into complicated bow and string dynamics, but as you might have read in the picture, that was far too complicated for a 3 week project.

Appendix B

Articles about the drawbacks of IFs:

-

Hate journal impact factors? New study gives you one more reason – Science News

-

Why not use the Journal Impact Factor: a Seven Point Primer – Byte Size Biology Blog

-

Impact Factor Distortions – Science, Editorial

-

Funding and findings: the impact factor – The Guardian

-

The Impact of Impact Factors: Good for Business but Bad for Science – Papers from Sidcup Blog

-

Higher Impact Factor: Better Journal? Not a Necessity – J Indian Acad Forensic Med. Review Article

Yes, these articles are all about why impact factors are less than desirable. Going through the literature, I couldn’t really find any blog/publication/whatever talking at length why IF is a good thing. Articles discussing pros and cons generally just mention one pro: it gives an accepted, easy-to-understand method of estimating the relative value of a journal to a field. That’s it.

Reblogged this on Ayodeji T. Bode-Oke and commented:

Great post!

LikeLike

Thank you! 🙂

LikeLike

I’m an undergraduate in my senior yr working on my manuscript for publication in a student journal. This article is fantastic! Thank you.

LikeLike